Why This Blogpost Matters: Understanding the Unconscious in Everyday Life

Many people turn to therapy when they find themselves stuck in patterns of unhappiness, questioning their self-worth, or struggling with relationships. But understanding the unconscious mind isn’t just for those actively seeking therapy—it’s valuable for anyone interested in human behaviour, emotions, and the hidden forces that shape our choices.

This blogpost explores the subtle yet powerful ways our past experiences, internalised beliefs, and unconscious desires influence our daily lives. Drawing on insights from the British Psychoanalytic School, it offers a deeper understanding of why we compare ourselves to others, why external validation can feel so crucial, and how psychodynamic therapy can help break these cycles. Whether you are in search of an accredited, experienced therapist or simply curious about the subconscious mind, this article provides a thoughtful exploration of the psychological forces that drive us all.

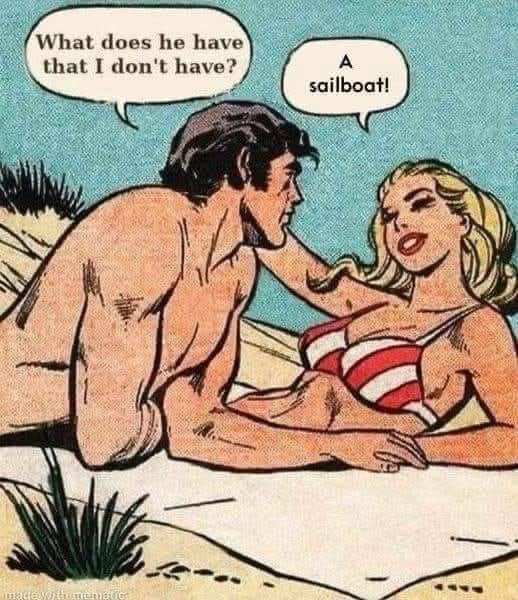

In a comic-style image that recently made the rounds on social media, a man and a woman lounge on a beach. He asks, “What does he have that I don’t?” and she bluntly replies, “A sailboat!” The humour lies in its stark realism—the painful realisation that, sometimes, the attributes we believe matter in relationships (personality, connection, shared values) may be trumped by something as material as a possession. Yet beneath the humour lies a deeper psychological truth about competition, self-worth, and the human tendency to seek validation in ways that may ultimately leave us feeling empty.

The British Psychoanalytic School: Competition, Envy, and Object Relations

British psychoanalysis, particularly through the work of figures like Melanie Klein, Donald Winnicott, and Wilfred Bion, has long explored the tension between inner emotional worlds and external realities. Klein’s work on envy and projective identification is particularly relevant here. She argued that from infancy, we struggle with feelings of envy towards the “good object” (often the mother or primary caregiver), experiencing both love and resentment toward what we perceive as desirable but unattainable. This duality can persist into adulthood, shaping our relationships in ways that leave us oscillating between feelings of inadequacy and defensive superiority.

In the case of our beachside couple, the man’s question (“What does he have that I don’t?”) reveals a longing for reassurance—an unconscious hope that the woman will affirm his unique worth. Yet her response (“A sailboat!”) lands as a brutal reality check: his rival possesses a tangible advantage, one that, at least in this instance, outweighs the intangible qualities he hoped would define his desirability.

Winnicott’s theory of the “true self” and “false self” also offers insight. When a person grows up in an environment that prioritises external achievement over authentic emotional experience, they may develop a “false self”—a persona curated to gain approval and ward off rejection. The man’s question suggests a moment of existential crisis: Is his self-worth contingent on external markers of success, like a sailboat? Or is there a deeper, more authentic sense of self that remains valid, irrespective of material competition?

The Psychodynamic Trap of Comparison and Unhappiness

Many individuals find themselves caught in cycles of comparison and unhappiness, unable to derive satisfaction from their accomplishments or relationships. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced in an era dominated by social media, where curated displays of wealth, beauty, and success foster a sense of perpetual inadequacy.

Freud’s early work on the repetition compulsion—our tendency to unconsciously recreate unresolved conflicts—helps explain why some people continually find themselves in situations where they feel overshadowed or unworthy. If, for example, someone grew up feeling that their achievements were never enough to secure parental love, they may unconsciously seek out relationships that replay this dynamic, aligning themselves with partners who reinforce a sense of deficiency.

Psychodynamic therapy can help individuals identify and break free from these patterns. By exploring early relational experiences and unconscious beliefs, clients can begin to differentiate between external pressures and their intrinsic sense of self-worth.

How Psychodynamic Therapy Helps Break the Cycle of Unhappiness

For those who, like the man in the comic, struggle with feelings of inadequacy, psychodynamic therapy offers a space to explore underlying emotions and relational patterns. Drawing on British object relations theory, a psychodynamic therapist might help a client uncover deeply embedded fears of not being “good enough” unless they possess tangible symbols of success.

1. Recognising Internalised Scripts

Psychodynamic therapy encourages clients to examine the internalised narratives that shape their self-perception. If someone has long equated worth with material success, they may feel undeserving of love unless they achieve a certain status. Therapy can help bring these unconscious beliefs into awareness, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of self-worth.

2. Exploring Envy and Desire

Kleinian psychoanalysis suggests that envy is often disavowed and projected onto others. A person might rationalise their unhappiness as stemming from external circumstances (“If only I had what he has, I’d be happy”), rather than confronting their deeper anxieties about self-worth. Therapy provides a setting in which these emotions can be acknowledged and worked through, rather than acted out in self-defeating patterns of competition and resentment.

3. Developing a More Stable Sense of Self

Winnicott’s concept of the “true self” is central to psychodynamic work. A therapist helps clients reconnect with aspects of themselves that have been suppressed in the pursuit of external validation. This process fosters a greater sense of authenticity, reducing reliance on external markers of success as a means of securing self-esteem.

4. Breaking the Repetition Compulsion

By bringing unconscious patterns to light, therapy allows clients to make different choices. Someone who has spent years seeking partners who reinforce their feelings of inadequacy may begin to recognise and challenge this pattern, making room for healthier, more reciprocal relationships.

Beyond the Sailboat: Reframing Self-Worth

Returning to the comic’s punchline, the question remains: What does he have that I don’t? If the answer is merely a sailboat, then perhaps the more important question is why that fact carries such weight. A psychodynamic perspective invites us to consider how much of our self-worth is shaped by comparisons, unconscious longings, and past relational wounds. By engaging in deep self-exploration, we can move beyond surface-level markers of success and toward a more fulfilling, authentic sense of self.

In a world that often prioritises external validation over inner security, psychodynamic therapy offers a crucial counterbalance. It helps individuals disentangle their self-worth from material competition, recognise destructive relational patterns, and cultivate a more enduring sense of identity.

And, after all, even if one doesn’t own a sailboat, one can still enjoy the sea.

By Ari Sotiriou M.A. psychotherapist

asotiriou@online-therapy-clinic.com

07899993362